Whilst motorcycling is a passion thing for many people and passion tends to make us blind to glaring faults, there are some motorcycles that were simply so bad in one or more areas that no-one, not even the manufacturers who gave birth to them, can find a good thing to say about them. We’re not even talking about particularly dangerous motorcycles, just ones that missed the mark so comprehensively that you have to wonder what they were thinking in the first place.

Then again, you have to wonder who is worse: the manufacturer for building it or the customer for buying it! So here, in no particular order, is our list of the ten worst motorcycles made since 1970, which is the date the Japanese started to take over the world and supposedly showed everyone how to build a good motorcycle.

10 Any 1970s Harley-Davidson

By the time the 1970s came around, Harley-Davidson wasn’t exactly in good health as a company and this led to the takeover by American Machine and Foundry, or AMF. The only problem was, AMF had no experience of building motorcycles or dealing with motorcycle customers, and by this time, a Harley-Davidson motorcycle was looking distinctly old-fashioned.

The engine was basically the old knucklehead unit which was down on power and, the more Harley engineers tried to coax more power out of it, the more the reliability worsened. It wasn’t just the engines, either: build quality suffered on the whole bike, and the dated styling didn’t help either. Vibration got worse and worse, and by the time the management staged a buy-out, it was a miracle there was any company left to buy.

9 Bimota V-Due

By 1997, even if two-stroke road motorcycles were rare, Grand Prix racing was still two-stroke powered, ever-improving engine management systems making them not only more powerful, but also more ridable. The Japanese manufacturers sold road-going race replicas which were highly covetable, but they weren’t available in the U.S.

So, when Bimota announced a clean burning two-stroke - the V-Due - using its own direct injection fuel system, anticipation was high. That anticipation turned sour when the fuel injection system turned out to be completely rubbish: it simply didn’t work properly, leaving the rider with either no power whatsoever or a sudden burst of full power, generally when you needed it least, such as mid-corner. As electronic traction control didn’t exist, this random on-off power delivery made things interesting. Bimota never got it right, and it ended up bankrupting the company.

8 Kawasaki H1 500 And H2 750

In the 1960s, the Japanese way to better performance was through more, more and yet more power. The trouble is, they forgot to beef up the chassis to cope with all the power. Things came to a head in 1969 with the Kawasaki H1 500 fitted with a two-stroke three-cylinder engine pushing out 60 horsepower.

This gave the H1 incredible acceleration but, unfortunately, the chassis and suspension simply wasn’t up to the task of containing it with the result that cornering at speed was strictly for the experts. Naturally, hardly anyone was an expert and the H1 was, to put it mildly, dangerous. Things didn’t get better with the 1972 H2 750cc model, which had yet more power - 74 horsepower - and which would become known as the ‘Widowmaker’ for the number of wives it turned into widows. Beautiful but dangerously flawed.

7 Victory V92C

Victory Motorcycles appeared in 1998, an attempt by parent company Polaris to capture some of the lucrative Harley-Davidson/cruiser market. If later, 2010-onwards models were excellent alternatives to the products of Milwaukee, then the early models were pretty dire. It wasn’t that they were bad motorcycles per se, but Polaris decided, for whatever reason, to release them before sufficient time had been spent ironing out problems, most notably around the clutch and transmission: if you think a Harley transmission is agricultural, then it is nothing compared to that of the Victory V92C. The styling was an uncomfortable mix of Harley-Davidson and Japanese cruisers, such as the Kawasaki Vulcan (see below) and Victory are lucky it didn’t sink the company without trace before it had even learned to swim.

6 Kawasaki Vulcan 2000

There are many fans of Japanese cruisers, even if they are slightly anodyne facsimiles of the ‘real’ thing, i.e. Harley-Davidson. Where the Japanese got it wrong was in assuming that what the market wanted was ever bigger models. The Vulcan 2000 weighed in at a not inconsiderable 820 pounds and the weight seemed to transfer itself to the controls as well: the clutch needed the strength of Hercules which might not have been a problem with 121 foot pounds of torque on offer, meaning that a mere twist of the right wrist had you rocketing forward, but the low rev limit meant you had to change up through the gears often when moving. The seat was too wide and uncomfortable, the ergonomics plain odd and the style dubious, as was the street cred of riding one. It’s still around in 1700 Voyager and Vaquero form, but now they’re fully dressed touring bikes so even heavier than ever!

5 Suzuki B-King

The B-King is not on this list for what it is, but for what it could have been. Launched at the 2001 Tokyo Motor Show, the thought of a naked, supercharged Hayabusa, with 240 horsepower, dripping in exotic materials such as carbon fiber, stainless steel and leather (?) was one thing, but the way it looked was something else again: Batman had placed an order, apparently…

It featured an advanced computer system with self-diagnostics, advanced telemetry, and GPS-based weather warning systems that were going to be accessible via mobile phone – the information was going to be projected onto the inside of the helmet visor Suzuki was going to make - and it featured fingerprint recognition for the ignition. When the production version of the B-King arrived in 2007, the power was ‘only’ 164 horsepower, the electronics had gone, the wacky styling just looked old-fashioned, it was overweight and didn’t handle all that well.

4 Honda DN-01

The problem with the Honda DN-01 (Dream New - Concept One or, as one unkind wag who worked at a Honda dealership had it, ‘Do Not Order One’…) was that it couldn’t really make up its mind what it was: was it a large scooter, a cruiser or a sport bike? The latter was a bit of a joke as it was powered by a 680cc V-Twin engine, driving through a continuously variable transmission, although Honda chose to call theirs HFT, or Human Friendly Transmission.

As a scooter, it was simply too big and as a cruiser it was just too weird looking, especially next to traditional cruisers from Harley-Davidson. Being a Honda, there was nothing wrong with the quality of the engineering or fit and finish but a price tag of $14,599 in 2009 was simply too much, even if what you were buying was unique (in that you’d never see another one on the road).

3 Yamaha YZF-R1 (2015-onwards)

By 2015, the superbike market was shrinking, which is a shame as the liter sport bikes were better than ever, reaching a pinnacle of perfection of engine, chassis and electronics that has remained relatively linear from that day to this. Whereas bikes such as Honda’s Fireblade were models of accessibility for any skill level of rider, flattering the inexperienced and thrilling the experienced alike, the Yamaha YZF-R1 was one of the most torturous motorcycles to ride ever, in the history of motorcycling.

The foot pegs were mounted too high, the seat was a device of torture and the reach to the handlebars too extreme: taken all together, they spelled nothing but pain, which was a shame as the engine and chassis dynamics were among the best in class. Why would you subject yourself to this, when you could have a much nicer time on a Yamaha MT-10, which is essentially the same bike, just comfortable!

2 Harley-Davidson Street 750/Street Rod

OK, we know exactly what Harley-Davidson was trying to do with the Street 750, and it was a noble cause, trying to tempt new and younger riders to the fold, something the company desperately needed to do if it was to survive for another 100 years. Sadly, H-D had absolutely no idea what younger riders wanted and this became apparent when the Street 750 was launched. Apparently, what young riders want is something so basic it hardly classes as a motorcycle!

The V-twin engine was about the only thing that linked the Street 750 to any other Harley-Davidson: in accordance with common H-D practice, horsepower wasn’t revealed, but this might have been because they were so embarrassed about how little there was. Things got a little better when the Street Rod version was launched - more power along with twin front discs and more cornering ground clearance, but the ergonomics were still terrible, and the model was quietly dropped in 2021.

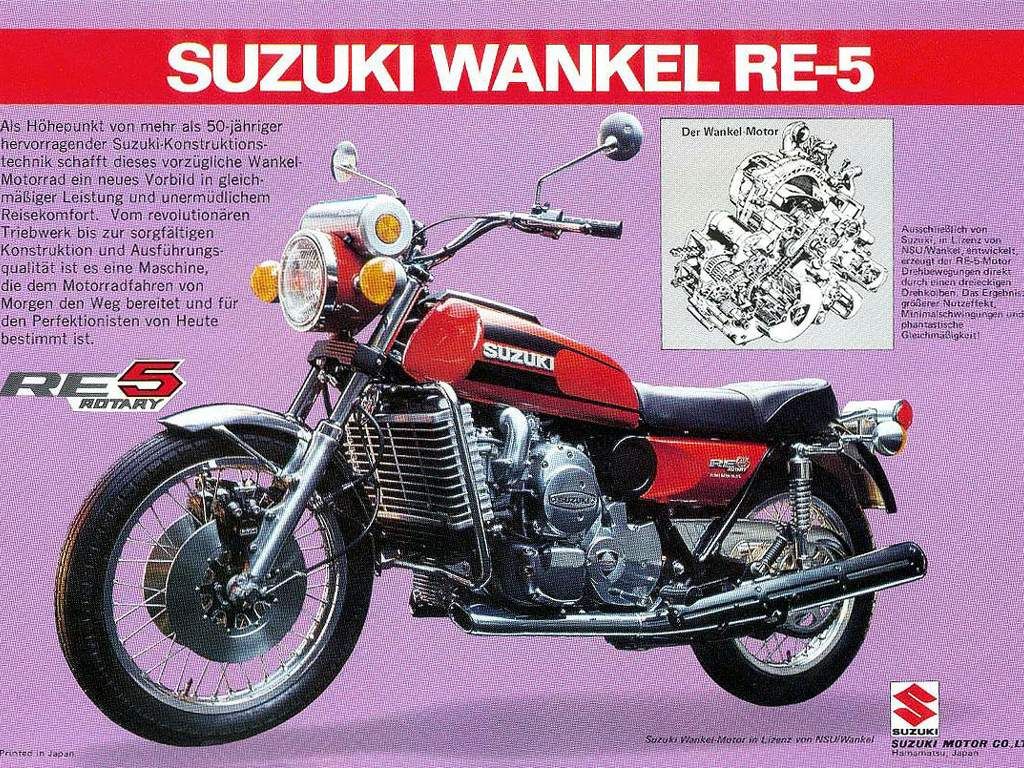

1 Suzuki RE5

One of the few motorcycles to ever appear with a Wankel rotary combustion engine, as ‘perfected’ by German manufacturer NSU. Alarm bells should have rung when details of the warranty were revealed: a full engine replacement for any engine problem within the first 12 months or 12,000 miles. Then, it was unusually heavy and complex.

Rotary engines produce a lot of heat so the RE5 had both water and oil-cooling, double-skinned exhaust pipes, two sets of ignition points, three oil reservoirs and two oil pumps. It also had no less than five cables from the twist grip controlling the primary carburetor butterfly, a valve in the port valve and oil supply (total loss) to the combustion chamber. The styling, by Guigiaro, with its ‘tin can’ instrument cluster with slide open Perspex cover and a similar-shaped rear tail light unit was also divisive. The only saving grace was the handling, which was better than many contemporary Japanese sport bikes. Cycle World magazine said the RE5 was ‘expensive, over-complicated, underpowered, and hideous.’ Not the stuff of which legends are made.